Introduction

There is a long history of political campaigns utilizing music in an effort to refine and shape a message. Music has a powerful ability to convey a message and communicate with an audience on a more emotional and personal level than many other forms of political messaging. For example, in 1952, the Eisenhower campaign commissioned the creation of the jingle “I Like Ike” in an effort to gain voter support. The jingle contained catchy lyrics, and was basically an advertisement that promoted Eisenhower for president. This jingle was effective because it was unique to Eisenhower, and the catchy tune had an “ear worm” effect on the listener. This jingle marked the beginning of political campaigns using musical messaging to communicate with voters and reinforce campaign efforts.

However, as time has passed, the way musical messaging is integrated into political campaigns has evolved from the use of jingles into the use of popular music. With this evolution, a long history of political candidates and politicians using music for their campaigns without proper permission from the artist themselves has developed. The improper use of music has led to a great deal of controversy between the music industry and politicians. In some cases, these controversies have even led to lawsuits. The most controversial modern day example of this is Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016. During Donald Trump’s campaign trail, many artists refused to allow him to use their music during his events, and most would even refuse to perform at his rallies or inauguration because they did not want to be associated with Trump’s controversial platform and reputation. Music is well-known for being a powerful medium that has the ability to convey a message or belief, which has made it a popular form of political messaging in campaigns. Political candidates are known for using music in their campaigns and rallies in an effort to reinforce their beliefs, or further state their position on a particular cause. However, musical artists have been known to object to this use and have enforced legal charges or even lawsuits against candidates that use their music without proper permission.

Integration of Music into Political Campaigns

Music has the ability to convey powerful messages and sentiments to its listener, which has made it an effective way to communicate and reinforce the central beliefs of a political campaigns. In order to effectively accomplish this, artists will often use various musical and extramusical tools that make their music a good medium for people, such as politicians, to use to support or reinforce their beliefs on a particular cause. Politicians will also use well-known artists’ music and live performances in an attempt to assert that the artists themselves are endorsing or supporting the candidate and their platform in order to influence voters. For example, Hilary Clinton was able to arrange for performances from numerous artists, such as Jay Z and Beyoncé, to perform at one of her campaign concerts, during which the artists expressed their support for her and her campaign.

In addition, music has a way of uniting people and making the country feel “whole.” For example, the “Star-Spangled Banner” continuously unites the general public at many different kinds of events, and often evokes feelings of pride and unity among the audience. Music also has the ability to provide the listener with a unique perspective of a way to view social life, which is an important aspect of the United States’ democracy. Justin Patch provides his own view on the use of music in political campaigns in his article “Notes on Deconstructing the Populism: Music on the Campaign Trail, 2012 and 2016.” In this article, Patch explores how music has been used in the presidential campaigns of 2012 and 2016, and how it was important to both elections. In addition, he also investigates which specific genres are a good fit for use in a political campaign: “In electoral politics, popular music is powerful for contradictory reasons. Pop is as politically significant for its characteristics of broad appeal, vapid, predictable lyrics, repetitive structures, and normative sentimentality as it is for its double entendre, coding, subversion, locality, and liberatory politics” (Patch 370). Patch then supports this assertion by reflecting on how Pop music is received at the consumer level, and how this reception contributes to the genre’s effectiveness within a political campaign. This assertion is also evidenced by the fact that many candidates have used music from the Pop genre within their political campaigns to appeal to a large portion of voters.

How Artists’ Rights Fit into Campaigns

Although many political candidates use music to reinforce their platform, not all of them take the proper steps to secure the rights for using the music in their campaigns. The use of various artists’ music in political campaigns without permission has been a controversial and ongoing battle. In 1984, Bruce Springsteen denied Ronald Reagan the right to using his song “Born in the U.S.A.” in Reagan’s campaign. However, this did not stop Reagan, which caused backlash from Springsteen himself: “Springsteen began to speak out against Reagan, questioning during a show whether Reagan actually listened to his music” (Chao 1). Therefore, these battles have caused problems for both the artists and the candidates themselves. Many attribute this issue to the fact that artists feel that by performing or allowing their music to be played at a campaign event or rally it will signal to the audience that the artist is endorsing that particular candidate and their views. In “The Campaign Tour: Pop Musicians Get on the Bus (Mostly Clinton’s),” Joe Coscarelli outlines the battles between artists and candidates during the 2016 presidential election. Coscarelli asserts that more artists were taking Clinton’s side and opting to perform at her events versus Trump’s: “Scooter Braun, a manager for influential acts including Mr. West and Justin Bieber, has been outspoken about his support for Mrs. Clinton. But he acknowledged that some of his clients had opted not to use their platforms for risk of ‘alienating part of their fan base who disagrees with them’” (Coscarelli 1). This perspective from Scooter Braun is important because it outlines one of the primary concerns that many artists have about allowing their music to be used in political campaigns. It is possible that this concern has been the basis of the controversy that has led to the battle about political campaigns’ use of artists’ music without permission. In addition, artists assert that they have property rights to their music, which has historically led to controversy, and even lawsuits, between the artist and the candidate.

Artists Take Action

Artists have often been so angry about their music being used at political events without permission that some of them have pursued lawsuits against the candidates they feel are guilty of this. Many of these lawsuits have been based on the fact that artists view their music as their own ‘property’ and that they have the right to dictate when and where it is performed. For example, the group, “The Heavy,” opposed the use of their song “How You Like Me Now?” in Newt Gingrich’s campaign so much that they pursued legal action: “Gingrich was served with a cease-and-desist notice by Montreal-based music publisher Third Side Music on behalf of the Heavy, for playing their song at a rally in Florida” (Chao 1). Although this seems extreme, the battle between Gingrich and The Heavy shows how far artists are willing to go to protect their music. An additional example is the battle between Don Henley and Chuck DeVore. This battle was based on the fact that DeVore had created a parody of one of Henley’s songs for use in his political campaign: “By 2010, musicians had taken politicians to trial over non-approved use of their music, but when Henley sued DeVore, it marked the first time that such a court case involved a parody. The California Republican senatorial candidate had turned Henley’s song “The Boys of Summer” into a takedown of Obama and liberalism called “The Hope of November” (Chao 1). Chao further asserts that much of the anger that led to this controversy was due to the fact that Henley was an Obama supporter, and he was bothered that DeVore was attempting to use his song to bad-mouth Obama. This is an example of an artist not wanting their music or character to be associated with the values or platform that a candidate represents. Therefore, although not all artists have taken legal action against candidates using their songs without permission, the possibility of lawsuit and legal action has altered the campaign environment. As a result, candidates must proceed with caution when using musical messaging within their campaigns.

Modern Day Campaign Struggles

In 2016-2017, one of the most controversial candidates in United States’ history, Donald Trump, had issues with various music artists. Many artists were so against Donald Trump’s controversial campaign that they would refuse Trump the right to use their music in his campaign events or rallies. In addition, many artists even refused the opportunity for a live performance at his rallies as well. As in many other examples of artists’ refusal to perform, many artists felt that by performing at, or allowing their music to be played at one of Trump’s events would lead to the general public’s assumption that the artist themselves endorsed Trump and his controversial character. In addition to concerns about public backlash, many artists felt that by performing at one of his events, they would violate their own moral character since they did not approve of his campaign platform. For example, after withdrawing from performing at a Trump event, Jennifer Holliday announced: “’Regretfully, I did not take into consideration that my performing for the concert would actually instead be taken as a political act against my own personal beliefs and be mistaken for support of Donald Trump and Mike Pence’” (Holub 1). This opposition even extended to Trump’s inauguration after his election, for which he struggled to find performers. The list of artists who refused to perform at Donald Trump’s election is detailed in an article written by Christian Holub: “Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration will take place Jan. 20 in Washington, D.C., but so far, the president-elect has had some difficulty assembling a star-powered lineup for the ceremony. Over the last month or so, more and more musicians have publicly declined to perform — even those who Trump has praised or have a previous relationship with the president-elect” (Holub 1). The list of artists who refused to perform at the inauguration included over 15 artists, which is notable given the level of publicity the artists would have received for the performance.

Works Cited

alliefox25. “1952 Eisenhower Political Ad – I Like Ike – Presidential Campaign Ad.” YouTube, YouTube, 14 Feb. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=YmCDaXeDRI4.

CBSNewsOnline. “Jay Z, Beyoncé, Big Sean, Chance the Rapper & More Perform at Clinton Concert.” YouTube, YouTube, 4 Nov. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyYBtqj7Yks.

Chao, Eveline. “35 Musicians Who Told Politicians to Stop Using Their Songs.” Rolling Stone, 8 July 2015, www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/stop-using-my-song-34-artists-who-fought-politicians-over-their-music-20150708/bruce-springsteen-vs-ronald-reagan-bob-dole-and-pat-buchanan-20150629.

Coscarelli, Joe. “The Campaign Tour: Pop Musicians Get on the Bus (Mostly Clinton’s).” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 Nov. 2016, www.nytimes.com/2016/11/03/arts/music/election-concerts-jay-z-voter-registration.html.

Holub, Christian. “All the Artists Who Won’t Perform at Donald Trump’s Inauguration.” EW.com, 10 Jan. 2017, ew.com/music/2017/01/10/donald-trump-inauguration-artists-who-wont-perform/.

Patch, Justin. “Notes on Deconstructing the Populism: Music on the Campaign Trail, 2012 and 2016.” American Music, vol. 34, no. 3, 2016, p. 365., doi:10.5406/americanmusic.34.3.0365.

by Meagan Dobbins

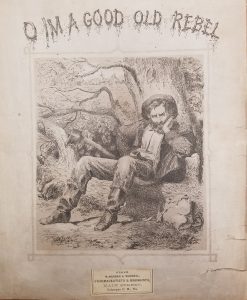

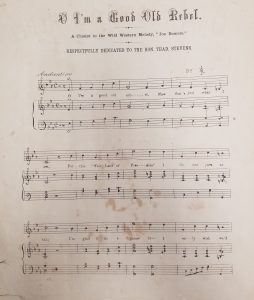

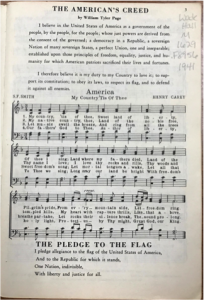

A nation that wants to create patriotism and nationalism during wartime had to produce a lot of records and songbooks. This desire to spread awareness and keep

A nation that wants to create patriotism and nationalism during wartime had to produce a lot of records and songbooks. This desire to spread awareness and keep