Historical Background

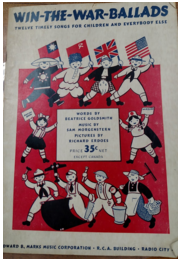

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent involvement of America in World War II, artists produced a veritable flood of patriotic music in order to support the efforts both of the American soldiers and of the civilians, particularly women and children. One example of music encouraging the efforts at home is found in the Hoole Special Collections Library at the University of Alabama, in the form of a paperback compilation of children’s songs. On a colorful title page, which depicts children from several Allied nations, the collection proclaims its contents to be a set of Win-The-War-Ballads: Twelve Timely Songs for Children and Everybody Else. Like many songbooks of the day, the collection involved three contributors: Beatrice Goldsmith, author of the lyrics; Richard Erdoes, the illustrator; and Sam Morgenstern, who composed the music. Within its pages, Win-The-War-Ballads includes numerous individual songs, each with a different message regarding the ways in which children and their families can bolster the war effort on the homefront.

During this time period, galvanizing the masses became an imperative for both the Allied and Axis forces, as psychological warfare in the form of propaganda played a huge role in the political culture of the era (Szasz 530). Much American propaganda centered on enlightening civilians in the domestic sphere on how better to serve their country from home. Offering one example of such propaganda, the Win-The-War-Ballads provides an exceedingly cheerful message urging children to take part in the war effort from home, with songs discussing topics from victory gardens to the proper procedure during a blackout. With its blend of musical and visual rhetoric, the piece brought forth a successful brand of propaganda that seems eerie when divorced from the context of war paranoia.

Propaganda in Music

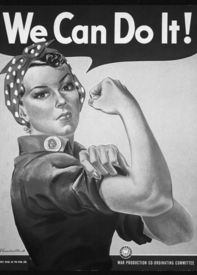

Much like Win-the-War-Ballads, the propaganda of the famous character “Rosie the Riveter” involved both visual and musical components. In addition to the posters bearing her image, The Four Vagabonds performed a song by the same name as the iconic girl on the poster. The melody of the piece is jaunty and bright, and the story shares a similar message to those in Win-the-War-Ballads: contributing to the war effort was vital and the patriotic duty of American citizens. In “Rosie the Riveter,” this message is achieved through uplifting lyrics, as the Four Vagabonds proclaim that Rosie “can do more than a male can do” and that she is keeping her Marine boyfriend safe by working for the war effort. The overall impression gained upon listening to the piece is one of encouragement and determination. Reading Win-the-War-Ballads, on the other hand, lacks that element of cheer; rather, its target audience and lyrical content is unnerving.

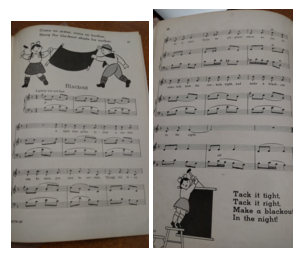

In songs like “Blackout,” which begins on page 17 of the source, this disturbing sensation becomes apparent. The song warns two smiling depictions of children, one boy and one girl, that, “A light that peeks behind a curtain can be seen, you may be certain.” This ominous tone, already seemingly inappropriate for the intended audience, becomes even more unsettling when paired with the following lyric: “[A light] as tiny as a star tells an airplane where you are.” With lyrics that discuss the proper methodology of concealing your house from warplanes, the tone of the piece appears almost vaguely threatening, with the implicit assumption being that failure to properly blackout your curtains results in the death of you and your family (an assumption supported by lyrics urging children to do this “for mother”). In light of this, the fact that this work was intended children is somewhat unnerving. Although the message it conveys offers important insight on safety precautions in wartime, the depiction of the children and the simplicity of the language used implies an intended age range of around 5 to 12, further compounding the sense of wrongness garnered from reading the song.

When one considers the bubbly and innocent target audience–children–juxtaposed with war’s harsh realities, the resulting cognitive dissonance conjures a sense of unease, particularly when observed from a modern perspective. Despite the apparent dissonance between the tone and the content of these songs, however, such depictions of war and the efforts required for victory were quite common during this time period. Regarding Win-the-War-Ballads, The New York Times described the pieces as “lively” and “catchy,” suggesting that record companies and radio shows play the songs should they be in need of an uplifting war ditty (H.T.). Viewed through this perspective, the propaganda almost seems even more insidious, due to the overwhelming normalisation of it during the era. Propaganda, though, hardly existed as a solely American phenomenon. Similar instances of propaganda appeared in every country involved in combat, garnering for support for the cause or, in some instances, attempting to dissuade it. For example, Germany attempted to discourage American efforts by dropping pamphlets in English that detailed how to fake illness to avoid combat – effectively attempting to diminish the size and scope of the United States’s fighting power (Szasz 530-531). Though there is some debate regarding the effectiveness of such attempts, one thing is patently obvious: propaganda during World War II was a fact of life, and its pervasiveness serves mainly to demonstrate the desperation of the time from every side of the war.

Win-the-War-Ballads and Visual Propaganda

Both at home and abroad, propaganda played an important role in shaping the public opinion and knowledge of the masses, a phenomenon that also diffused into the mediums of photograph and newspaper. In fact, one of the more progressive newspapers of the time, New York City’s PM’s Weekly, was a primary source for political discussion, debate, and enlightenment for American citizens in regards to the war effort. Its photography critic, Ralph Steiner, took foreign propaganda from Germany and analyzed it in the newspaper’s weekly production. The start of this slightly controversial yet highly effective news style can be clearly pinned to the article published on September 22, 1940. The article shocked and astounded the paper’s readers, as it depicted a reproduction of a picture of Hitler posing with children as though for a family portrait. This is where PM’s Weekly gained its fame: through the deconstruction of German propaganda and revealing to the American people the methods Hitler was using to deceive his people. Over the course of the war, PM’s Weekly released a plethora of articles on German media.

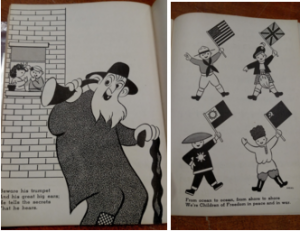

One of the most influential and recurring ideas seen in PM’s Weekly was, “In a sense, every photograph is a piece of propaganda” (Steiner). This lesson is highly relevant to the informed citizen, and its ideal can easily applied to Win-the-War-Ballads. Although the images depicted are illustrated, not photographed, they still act as propaganda in influencing musically inclined civilians and supporting the messages of the songs. For example, the image accompanying the song “Children of Freedom” shows four smiling kids waving flags from America, Russia, China, and Britain. Erdoes clearly made a conscious choice in the illustration for this piece, dutifully portraying a sense of unity and camaraderie among American civilians and the other Allied powers. Another prime example would be the caricature of a Jewish man for the song “Old Man Rumor.” Though originally German-born, Erdoes travelled to America a few years before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. His personal bias, however, can be seen in the stereotyped and exaggerated features of Old Man Rumor, as he was likely affected by the prevalent anti-semitism in Germany. The message of the song, though, remains clearly anti-German in its sentiments; with its lyrics, it gently reminds children not to speak of any information regarding the deployments of family members, using the titular Old Man Rumor as an obvious reference to Axis spies.

Propaganda and the Removal of Context

Unlike her musical counterpart, the original poster of Rosie the Riveter did not attempt to motivate or empower female workers. Although in modern society, Rosie is often cited as a symbol of feminism and encouragement, the intent behind her inception was not one of American propaganda; rather, her purpose was far more corporate. During World War II, the poster of Rosie the Riveter was commissioned by Westinghouse factories to encourage unity and motivation among its workers (both male and female), and not the government for factory recruitment. As a result, the classic depiction of Rosie that is so well-loved today was not widely known of during the war and became better known almost three decades later, in the early- to mid-1980s. These common misconceptions have only been strengthened and reinforced in the public mind through newspapers and other formal published documents, which cite historically inaccurate facts about Rosie (Kimble and Olson). Taken out of its original context and assigned a new meaning, Rosie the Riveter actually has a greater impact today than it did during the war. As a result, it is currently considered one of the most iconic wartime propaganda images in America.

In Win-the-War-Ballads, a similar phenomenon applies: due to its removal from the original context, the 21st century reader reacts to the music differently than its intended audience did. Despite receiving a positive critical review from a major publication, when reading and listening to Win-the-War-Ballads, the collection seems unsettling in retrospect. This eeriness comes from the cheerful, yet frightening, instruction manual for children, teaching them about their duties as Americans on the homefront. However, in the context of its respective time period, the songs accomplished their purpose rather successfully. The songs cleverly intertwined visual propaganda with “lively” children’s tunes in order to indoctrinate a generation of kids to support the American war effort. What seems sinister in the modern day was merely a fact of life for children of the era. Although such harsh realities are hard to swallow, preventative measures such as blackouts, rationing, and keeping secrets allowed for America’s successes during the war.

Works Cited

H.T. (1943, Jun 27). Lively War Song. New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/106631432?accountid=14472.

Kimble, James J., and Lester C Olson. “Visual Rhetoric Representing Rosie The Riveter: Myth And Misconception In J. Howard Miller’s ‘We Can Do It!’ Poster.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 4 (2007): 533. Project MUSE. Web. 23. 2016.

Morgenstern, Sam, and Beatrice Goldsmith. Win-The-War Ballads: Twelve Timely Songs For Children And Everybody Else. n.p.: New York : E. B. Marks, c1942., 1942. University ofpAlabama Libraries’ Classic Catalog.

Payne, Carol. “War, Lies, and the News Photo: Second World War Photographic Propaganda in “PM’s Weekly” (1940-1941)”. RACAR: revue d’art canadienne / Canadian Art Review 39.2 (2014): 29–42. Web.

Evans, Redd, and Jacob Loeb. Rosie the Riveter. The Four Vagabonds. Bluebird Records, 1943. MP3.

Szasz Ferenc Morton. “Pamphlets Away”: The Allied Propaganda Campaign Over Japan During The Last Months Of World War II.” Journal Of Popular Culture 42.3 (2009): 530-540. SocINDEX with Full Text. Web. 27 Feb. 2016.

Trevor Macks, Molly Giffin, and Hayes Favinger