Throughout recorded history, music has played a significant role in political affairs around the world. The American Civil War is a prime example of an era in which music had real-time political impact as well as long-lasting sentimental effect. Whether inspiring soldiers in battle, evoking patriotism amongst citizens on the home front, or masking the horrors of the war, music proved to be an effective weapon for both the Union and Confederate armies (Davis, Tubb). While a handful of songs from the Civil War era accomplished all of these tasks and made an everlasting mark on American history, few songs achieved such high accolades. Even songs that failed to achieve such high levels of success and fame, however, offer valuable insight about the cultural and political sentiment of a time from which we are so far removed.

The Battle Hymn of the Republic: an early success

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” was one of the most popular songs of the Civil War and is still sung across the nation today (Tubb). Created in November of 1861 by Julia Howe, the daughter of a successful Wall Street banker, the “Hymn” made its first public appearance on the front page of the Atlantic Monthly in 1862. The song, however, was not an entirely original creation. Touring a Union army camp near Washington D.C. with Reverend James Clarke and her husband Samuel Howe (a member of president Lincoln’s Military Sanitary Commission), Julia listened and sung along while soldiers sang their favorite war songs. After singing “John Brown’s Body”, a popular marching song about famous abolitionist John Brown, Reverend Clarke “was moved to suggest that Mrs. Howe pen new lyrics to the familiar tune” (Tubb). As Mrs. Howe tells it, she awoke the following morning with the sought after lines arranging themselves in her brain (Tubb). Howe’s creation of dramatically divine lyrics which promoted the Union’s cause, set to an older popular tune resulted in a hymn that would transcend over a century as one of the most recognizable pieces of American musical history.

The release of Julia Howe’s freshly adapted song in February of 1862 under the name of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” proved to be a substantial event for the Union. “Within a year this new hymn was being sung by civilians in the North, Union troops on the march, and even prisoners of war held in Confederate jails” (“John Brown’s Body…”). By adapting the lyrics of a pre-existing tune that was popular amongst militants, Howe created an anthem that embodied the quintessential war song. Benjamin Soskis accurately encompasses this notion when he explains, “Howe would provide both soldiers and civilians with a powerful statement of the North’s righteousness… God’s truth was ‘marching on’”. In addition to effectively boosting the morale of the entire Union, powerful hymns like this figuratively “minimized the suffering and death that haunted the battlefields and hospitals” (Davis 157), thus masking some of the horrors of war. While hundreds of other publishers attempted to produce pieces as impactful as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, few managed to achieve such prominent results.

The Union Solders Hymn: a mystery unfolds

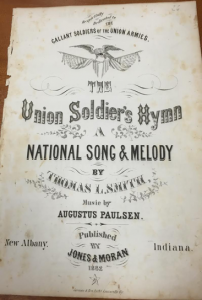

“The Union Soldiers Hymn” by Thomas L. Smith is one example of a piece that failed to make such a strong impression with the Union soldiers and the Northern public. Preserved in the Hoole Special Collections Library at the University of Alabama, the tattered, yellowing pages feature an aesthetically pleasing title page followed by two sweets of notated music. While “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” features four verses each followed by a chorus, “The Union Soldiers Hymn” has six verses that end in a refrain which varies slightly from verse to verse. Although both hymns had the ultimate purpose of raising support for the Union’s cause, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” achieved this goal and secured recognition as one of the most important musical pieces in American history while “The Union Soldiers Hymn” faded into an unrecognizable relic of the Civil War. This is evident in the lack of documentation and historical context pertaining to “The Union Soldiers Hymn” that is available today, compared to the multitude of information available on the creation and impact of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, as well as its prevalence in modern schools and churches. Though “The Union Soldiers Hymn” may not have achieved widespread popularity, it still displays the political attitude of the time, and offers insight to a culture vastly different than ours.

The Quest for Popular Publication

Such drastically different fates causes one to ponder the disparity in public perception between two pieces with such similar motifs. The primary and most discernible difference between the two hymns is lyrical content

Traditionally speaking, “The Union Soldiers Hymn” is not really a hymn, as it praises America and the flag rather than God. “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, on the other hand, serves as a tribute to God and a proclamation of faith, thus more accurately representing a typical hymn. One could speculate that the prominence of religion in “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” contributed to its popularity and efficacy, especially considering that the vast majority of Northern churches supported the Union’s fight (Moorehead). Furthermore, the inspiration for the creation of both pieces varies widely. By utilizing a well-known melody as the tune to her hymn, Julia Howe produced a piece that was instantly recognizable for most of the nation. The familiarity of Howe’s hymn encouraged participation amongst listeners, helping secure its popularity. Thomas Smith’s piece, however, lacked association to a well known tune, making the piece more foreign and less appealing to the mass public.“The Union Soldiers Hymn” is scored for voice and piano forte, and there is no accessible documentation regarding its existence, so one may reasonably infer that it was more of a “presentational performance”, one that was not sung by soldiers on the battle field or by the family at the kitchen table.

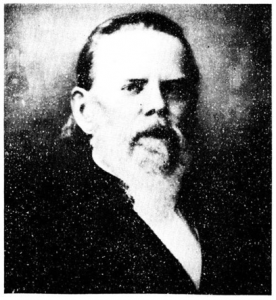

The presentational nature of “The Union Soldiers Hymn” raises speculation about the motivation behind the production of the piece. One might make the reasonable assumption that a publisher producing a Civil War hymn at the beginning of the Civil War intended for it to be sung by soldiers at camp or while marching, but in this case, further research suggests otherwise. The author, Thomas L. Smith, was a surgeon, a lawyer, and a politician (Lansing 123-126), but his only musical production was “The Union Soldiers Hymn”. The composer, Augustus Paulsen, is only known to have composed this piece. The publisher, Jones & Morgan, published the hymn and no other work under this publication name. Interestingly, the two men who published this piece, George Jones and Edwin B. Morgan were both successful businessmen. Jones was a banker in New Albany, NY who cofounded a newspaper called New-York Daily Times, currently known as New York Times (Jones). Morgan was a politician and an entrepreneur. He was the first president of Wells Fargo & Company as well as a director of American Express Company, and he represented the 25th congressional district in the House of Representatives from 1853 through 1859 (“MORGAN, Edwin Barber – Biographical Information”). While their careers varied, Jones and Morgan had an established business relationship before embarking on their publishing venture. In 1857, Morgan contributed part of the funds that allowed Jones to cofound New York Times (Adler). Given the fact that its author and publishers were relatively successful businessmen with no musical background, one could deduct that “The Union Soldiers Hymn” was produced for the purpose of generating profit. The following scenario, while speculative, offers evidence backed insight as to how and why “The Union Soldiers Hymn” came to publication. First, one must note the copyright mark on the bottom of the second page of the document, reading “Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1861…” (Natanson). This reveals that Thomas Smith potentially wrote the lyrics as a poem at the start of the war, with intent to distribute when he deemed most appropriate. After observing the success of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, Smith perhaps saw the opportunity to present his copyrighted poem in a form similar to Howe’s high-achieving hymn. Rushing to capitalize on this opportunity, Smith reached out to Jones (a man with publication abilities at his discretion), who may have been an old business acquaintance (through Smith’s careers in law, medicine, or politics), requesting his assistance in publishing the piece. From here, the unknown composer, Augustus Paulsen, was hired perhaps through friendship or for the sake of production cost and speed. Lithographical errors like irregular notation and notes falling on either side of their stem suggest that the printer was also hired due to acquaintanceship or out of necessity for fast, cheap production, rather than technical skill. Finally, published as “The Union Soldiers Hymn”, Smith’s original poem adapts a name that associates it with the already popular piece, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”.

The Civil War era produced hundreds of songs similar to “The Union Soldiers Hymn” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”. While few managed to achieve the powerful impact and long lasting recognition the Julia Howe’s hymn accomplished, the lesser known pieces that exist today still posses their own unique value. The lyrics, physical appearance, and production context of pieces like “The Union Soldiers Hymn” provide a rare glimpse into the culture of America 150 years ago. Pieces like this show not only what was happening at the time of production but also the attitude with which Americans viewed issues like the war, and for this reason, these long lost relics hold great value.

Primary Source Analysis

The physical document for “The Union Soldier’s Hymn” is in relatively good shape given its one-hundred and fifty-four year age. At first glance, one may notice a few stains, yellowing, and even some tears. The piece, however, is still readable, and even aesthetically pleasing.

The front cover features a visually appealing design displaying the title, author, composer, publisher, and printer. The title, author’s name, composer’s name, and publisher’s name are all presented in different, decorative fonts. The artistic precision of the title page suggests it was printed from a carved lithograph stone or plate.

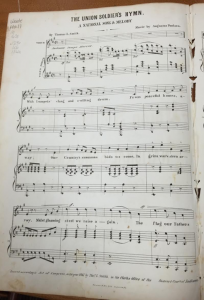

On the verso of the title page is the first page of notated music. At the top of this page is the title, “The Union Soldier’s Hymn,” written largely, with the subtitle “A National Song & Melody.” On the top left corner of the page, a few page numbers are hand-written in, though it seems to just be a catalog number for the University of Alabama’s cataloging process and therefore of little significance. The music itself appears in moderate notation, save for one significant difference: the stems of the notes do not lie consistently to the side of the notehead dictated by modern notation; this may indicate that the person who lithograph stone-carved this piece was in a hurry to finish, not wholly aware of the technicalities of writing formal sheet music, or a combination of the two. The bottom of the page pictured below indicates that the piece was “Entered according to Act of Congress,” (Smith) in 1861 by a District Court of Indiana.

The next and final page of the piece is much like the second page. It contains the remainder of the music, and then an additional five more verses to the hymn. In the seams of the sheet music are a series of tears that suggest that this piece was torn out of a larger book. This larger book was perhaps an official collection of similar pieces to “The Union Soldier’s Hymn,” or possibly from some individual’s personal collection of similar pieces.

The lyrics imply a heaven-ordained cause of going to war. For example, the line “That flag must wave o’er every foe forever, ever more!” from the fourth verse depicts the image of the army pursuing a just cause by going to battle, as it is necessary to protect their sacred nation (Smith). One particular lyric that distinctly highlights morale-boosting elements is in verse three when Thomas writes, “… our gallant heroes won,” (Smith). Any person singing this tune while going into battle will feel his spirits affected via recognition as a gallant hero.

Though the piece is technically a hymn, it is composed more like a march, with the musical tempo marking being “Andante Tempo Marcia,” or “A march played at walking speed,” (Smith) (“Goodwin’s High End-Glossary of Tempo Markings”) The upbeat tempo fits the morale-boosting lyrics of the song. Inclusion of a piano part further supports the theory that the piece was written more to be sold at large than performed by a marching army in actual battle.

Bibliography

Adler, John. “Doomed by Cartoon.” Google Books. Web. 23 Mar. 2016. <https:// books.google.com/books?id=z6YjB5FnKgwC>.

Bowman, John S., and Stephen Currie. “Music of the 1860’s; Patriotic Songs of the Era.” Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations. Web. 06 Mar. 2016.

“Civil War Music: The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations. Date Published N/A. Web. 23 Mar. 2016.

“Goodwin’s High End-Glossary of Tempo Markings.” Goodwin’s High End – Glossary of Tempo Marking. Date N/A. Web. 23. Mar. 2016.

“John Brown’s Body The Battle Hymn of the Republic by Julia Ward Howe Historical Period: Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1877.” John Brown’s Body. Web. 23 Mar. 2016. <http://www.loc.gov/teachers/lyrical/songs/john_brown.html>.

James A. Davis. “Music and Gallantry in Combat During the American Civil War”. American Music 28.2 (2010): 141–172. Web. 22 Mar. 2016.

Jones, George. “George Jones Papers 1825-1894 [bulk 1860-1887].” George Jones Papers. Web. 23 Mar. 2016. <http://archives.nypl.org/mss/1590>.

Lansing, Dororthy I. “TEHS – Quarterly Archives.” TEHS – Quarterly Archives. Web. 23 Mar. 2016. <http://www.tehistory.org/hqda/html/v18/v18n4p123.html>.

Members of the 26th North Carolina Infantry Band. Digital image. Americancivilwar.com. National Park Service; Gettysburg National Military Park. Web. <http://www.americancivilwar.com/Civil_War_Music/civil_war_music.html>.

Moorehead, James. “Religion in the Civil War: The Northern Perspective, The Nineteenth Century, Divining America: Religion in American History, TeacherServe, National Humanities Center.” Religion in the Civil War: The Northern Perspective, The Nineteenth Century, Divining America: Religion in American History, TeacherServe, National Humanities Center. Web. 23 Mar. 2016.

“MORGAN, Edwin Barber – Biographical Information.” MORGAN, Edwin Barber – Biographical Information. Web. 23 Mar. 2016. <http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=M000948>.

Natanson, Barbara. “A Grand Entry: Entered According to Act of Congress.” A Grand Entry: Entered According to Act of Congress. 29 July 2015. Web. 23 Mar. 2016.

Portrait, of Judge Thomas Lacey Smith. (Courtesy of the Supreme Court of the State of Indiana.). Digital image. Tehistory.org. Web. 6 Mar. 2016.

“Search Results from Civil War Sheet Music Collection.” The Library of Congress. Web. 23 Mar. 2016. <https://www.loc.gov/collection/civil-war-sheet-music/>.

Smith, Thomas L. “The Union Soldier’s Hymn.” N.d. New Albany, Indiana: Jones & Morgan, 1862.

Soskis, Benjamin. “How the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” Changed America—and the Life of the Woman Who Wrote It 150 Years Ago.” Slate.com. Web. 23 Mar. 2016.

Matthew Childress, Jack Fitzgerald, Tyler Smith