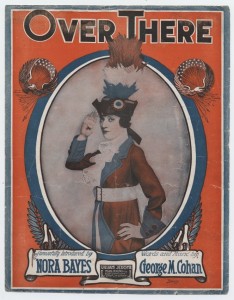

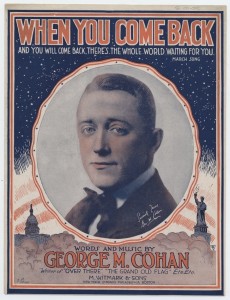

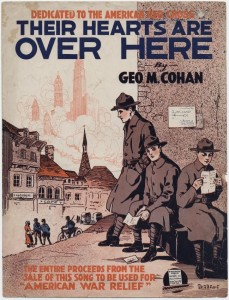

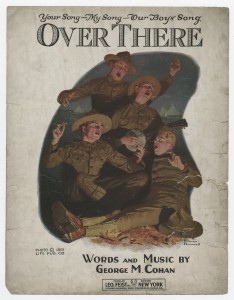

“Over There” was written on April 6, 1917 by the playwright George M. Cohan. He wrote this song in response to the newspaper headline that announced the United States’ declaration of war on Germany. At the beginning of the song’s life, it was a patriotic call to arms, but later became “the song of the war” (Morehouse 127) and became very popular among the people of the United States during World War I. The song sold very well in its audio recorded version as well as the sheet music. The sheet music was very common in the average American household during this time period and singing this song and others like it was one way that people cultivated patriotism in their everyday lives. Nora Bayes was the vocalist in the original recording of the song and it reached over one and a half million copies sold in the entirety of the song’s life where other songs of the same time period reached only 100,000 to 300,000 copies sold (Morehouse 127). Enrico Caruso, Billy Murray, Arthur Fields and Charles King also recorded the song helping to make it one of the most popular songs at the time.

The sheet music was printed four times with four different covers, each successive cover showing increasingly detailed artwork as the song grew in popularity. Around the time that Nora Bayes recorded the song, the sheet music featured a portrait of her, intended to associate the song with her fame and popularity as an entertainer. Another cover depicted men together singing and dancing. A third cover depicts William J. Reilly who was a popular singing soldier during the war. The thing that these three covers had in common were that they were artistically simple covers with few colors and no artist’s signature. The fourth cover published in 1918 on the cover of “Over There” was of four soldiers sitting around a fire singing together, but this image is very detailed, has many colors and shades and was a reprint of a famous painting by Norman Rockwell who was a famous painter at the time and would increase the cost of the printing of the music. The song has reappeared recently due to its popularity. In 2009 the US men’s national soccer team used the chorus in a campaign leading into the World Cup Finals. Recently the song was used in the movie Leatherheads in 2008. “Over There” has been used in many various films and TV shows although many times it is either just the melody or the lyrics.

Morehouse, Ward. George M. Cohan, Prince of the American Theater,. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1943. Print.

Cohan, George M., Louis Delamarre, and Norman Rockwell. Over There. n.p.: New York, 1918,

Feist Inc. ; London, England : Herman Darewski Music Pub. Co., [1918?], c1917. Music score. W.S. Hoole Library Rare Sheet Music Collection.

Michael Amling