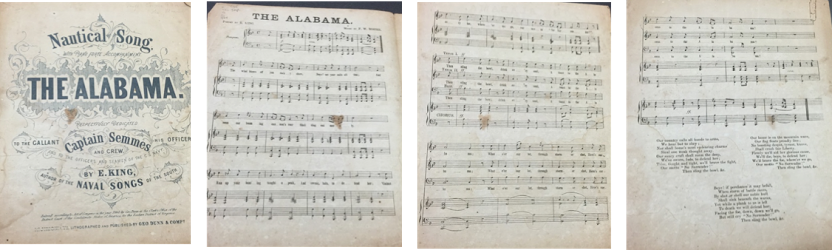

Held in the Hoole Special Collection Library at the University of Alabama is an original copy of sheet music for the naval song “The Alabama,” which was published in 1864. In the midst of the American Civil War, the music was composed by Fitz Williams Rosier and the lyrics were created by Edward King in order to commemorate the crew of the Confederate ship the CSS Alabama. The piece was written in response to a commission by a Confederate Act of Congress.

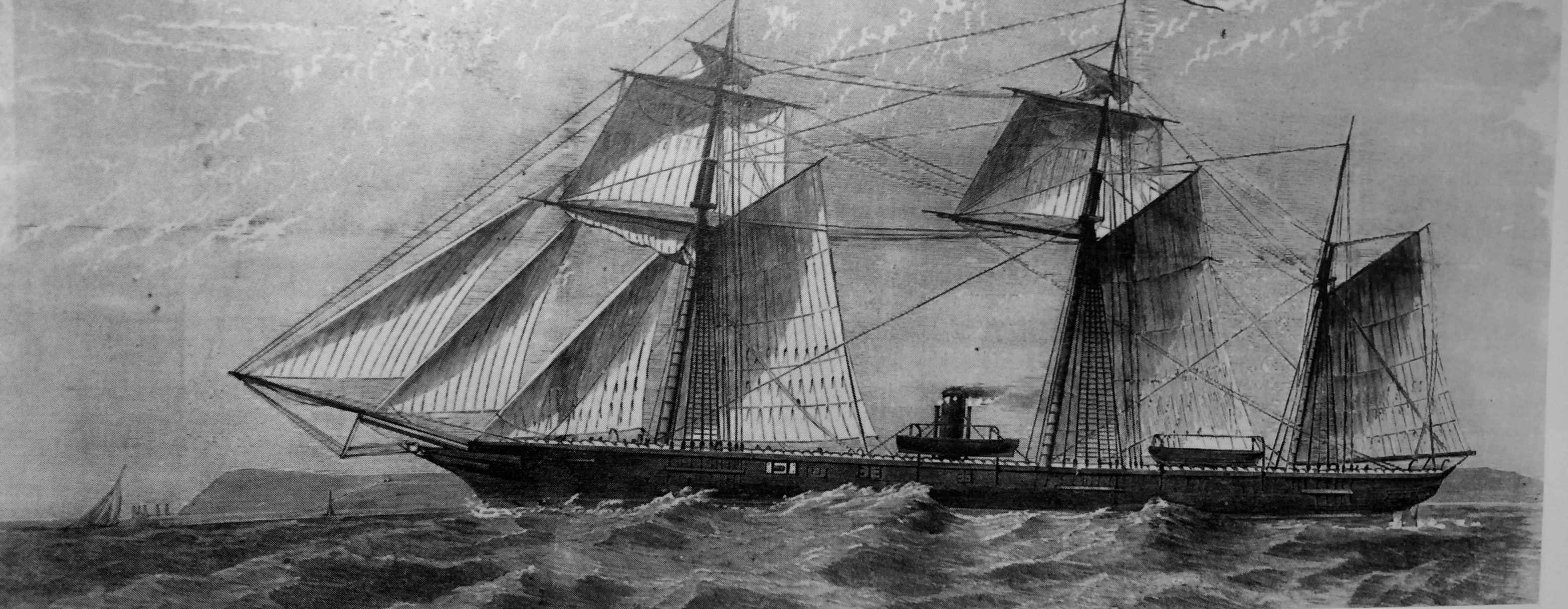

The career of the CSS Alabama spanned from 1862 to 1864. According to Charles M. Robinson III (The Shark of the Confederacy), the ship and its captain, Raphael Semmes, earned their place as confederate legends when they managed to wage a “single-handed war against Northern Commerce.” Crafted in Liverpool, the Alabama spent almost the entirety of its two years of service in the waters around Great Britain, never once docking at a port of the Confederate Republic it defended. During its two years at sea, the Alabama captured or destroyed over 80 merchantmen— ships used for commerce— and one warship; the Confederacy’s main mission was to thwart Union trade with European countries and ultimately block the Union’s search for a new source of cotton in the absence of Southern production (Robinson 1-3).

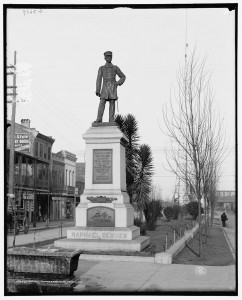

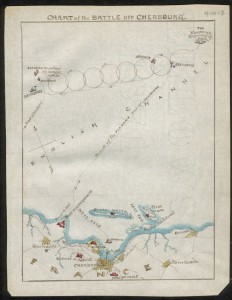

However, the Alabama would become most well known for its final moments on Sunday June 19, 1864, in Cherbourg Harbor of the coast of France in a battle against a Union ship called the Kearsarge. The crew of the Alabama became famous for their refusal to surrender even when their ship was damaged beyond all hope (Robinson 135-36). A newspaper article from the Daily Cleveland Herald written on July 7, 1864, recounted that “with great bravery the guns were kept ported till the muzzles were actually underwater, and the last shot from the doomed vessel was fired as she was setting down.” It was not until the ship’s stern was completely underwater that Captain Semmes gave the orders for his men to “save themselves as best they could.” It is estimated that the crew of the Alabama contained about 150 men and that 10 to 12 of the ship’s crew were killed during the Battle at Cherbourg. However, tales of the crew’s bravery and loyalty do not end with the sinking of their ship; eyewitness accounts from the Deerhound, a steam-yacht owned by an English family who set sail to watch the battle and later rescued Captain Semmes and many of his crew members from the wreckage of the ship, state that the “men were all very anxious about their Captain and were rejoiced to find that he had been saved.”

The song “The Alabama” is one of many pieces created by Confederate musicians to eulogize the ship’s final moments and more importantly to spread word of the crew’s immense bravery in a battle against an ironclad ship that far outmatched the firearms of the Alabama (Robinson 135-36). The song references accounts of the crew’s endurance in battle in its final verse when the men sing, “if perchance it may befall, when storm of battle raves, by shot or shell our noble hull shall sink beneath the waves… to death we will defend her, facing the foe, down, down we’ll go, but still cry ‘No Surrender!’” In 1864, when the war was coming to a close, the Confederacy was trying with all its might to bolster the morale of its army and citizens. Captain Semmes and his crew became symbols of what the Confederacy needed most in this stage of the war, “No Surrender.”

The sheet music edition of “The Alabama” is an embodiment not only of the Confederate spirit but also of printing methods and musical style of the time. The lithograph print held at Hoole is four pages long and is in good condition with only slight discoloration, a few stains that do not obscure any information, and pencil writing on the top left corner of the second page that appears to be a library call number.

The cover displays the song’s title, a dedication to Captain Semmes and the crew of the Alabama, the name of the lyricist, Edward King, an explanation that it was written in response to an Act of Congress in the year 1864, and that it was lithographed and published by Geo Dunn and Company in Richmond, VA. While there is no illustration on the cover, the words are arranged artfully and are decorated with swirls and leafy ornamentation printed in black ink.

The decorative flourishes and fluid lettering presented on the cover of “The Alabama” are typical of nineteenth century lithography. In The Rise of Early American Lithography and Antebellum Visual Culture, Erika Piola explains how lithography changed the style of printed documents: “The lettering, flourishes, and scrolls— the typography— used in job prints assumed a fluid, decorative appearance previously absent and not easily achieved through the cross-hatching and more linear cuts necessary in engraving” (131). While the engraving process had inherent typographic limitations, the lithographic process allowed for the more free-form illustrative style seen on “The Alabama”’s cover.

The first American lithograph was produced by Bass Otis in Philadelphia in 1819 (Piola 125). This manner of printing gained in popularity until by the 1860s it was the primary printing process (Piola 137). Based on the principle that oil and water do not mix, the lithographer uses a pen or brush to make grease-based crayon or ink marks on a flat piece of limestone. The grease marks are then acidulated, sealed by the application of a gum arabic and nitric acid solution. Next, the lithographer sponges the limestone with water to make the grease spots more receptive to the printing ink which is then applied to the stone, sticking to the greasy marks and being repelled from the damp, unmarked areas on the stone. From there the stone is placed in a press where the ink is transferred to the paper, producing the final product (Piola 126).

While lithography is best demonstrated on the cover page of the document, the next three pages contain the vocal melody, musical notation, lyrics, and piano accompaniment. In 1864 when “The Alabama” was composed, the piano was well-established as an instrument for music making at home and in small gathering places, such as churches and civic meeting halls. In 1851, 9,000 pianos were built and sold, and by 1860 that number had risen to 21,000. Increasing hand-in-hand with the piano’s popularity, sheet music was in high demand. Decorated with elaborate illustrations and given fancy titles, the front covers of sheet music were almost as important as the music contained inside, for the music itself could be of variable quality and similar to other pieces in an age when composers, in response to economic demand, wanted to release music as quickly as possible and to create music that was accessible to the masses who were mostly beginner and intermediate pianists. A small benefit of the Civil War is that it offered fresh material for composers as the divided nation developed an interest in patriotic songs, such as “The Alabama” (Cornelius). True to the uncomplicated nature of pieces from this time, “The Alabama” has an undemanding rhythm in common time with eight-bar phrases in the simple key of F.

Examining this primary source and its context reveals a great deal about its nature as a piece of patriotic propaganda. The sheet music for “The Alabama” utilized an efficient printing method, easy to learn musical notation, and the popularity of the piano as a household instrument in order to become an ideal vessel for spreading the inspiring story of the CSS Alabama and its crew as the war was coming to a close.

Works Cited

Bowock, Andrew. CSS Alabama: Anatomy of a Confederate Raider. Rochester: Chatham Publishing; 2002. Print.

Cornelius, Steven H. Music of the Civil War Era. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2004. Print. p 19-23.

Piola, Erika. “The Rise of Early American Lithography and Antebellum Visual Culture.” Winterthur Portfolio 48.2/ 3 (2014): 125-137. Art & Architecture Complete. Wev. 23 Sep 2015.

Robinson III, Charles M. Shark of the Confederacy. Annapolis: Naval Institute, 1995. 1-6, 135-149. Print.

Rosier, F. W., and E. King. The Alabama :. n.p.: Richmond : Geo. Dunn, 1864. University of Alabama Libraries’ Classic Catalog. Web. 5 Oct. 2015.

“The Sinking of the Alabama.” Daily Cleveland Herald [Cleveland, Ohio] 7 July 1864: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 5 Oct. 2015.

Elise Helton and Margaret Lawson