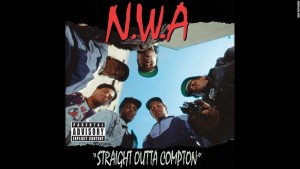

Straight Outta Compton is a certified double platinum album that was released August 9, 1988, by the rap group N.W.A. (McCann 368). In this album, group members O’Shea “Ice Cube” Jackson, Eric “Eazy-E” Wright, Lorenzo “MC Ren” Patterson, Antoine “DJ Yella” Carraby, and Andre “Dr. Dre” Young describe the everyday life of the black man in Compton, located in South Central Los Angeles. The album also sheds light on a domestic war that few Americans knew the true story behind: the war against police brutality and black-on-black violence.The album itself contains several songs that protest against police brutality in Los Angeles, such as “Straight Outta Compton” and “F*** the Police.” This “gangsta rap” displays what some consider to be an unpleasant side of rap music, highlighting the life endured by many black men who are struggling to live in a culture of gang violence, police brutality, and job inequality. Straight Outta Compton became the anthem for the anti-police brutality movement, and had violent and non-violent repercussions which harmed the L.A.P.D.’s public image after the album gained national attention.

N.W.A. is also renowned for outright threats to police officers. For example, MC Ren raps “I’m a sniper with a hell of a scope, taking out a cop or two, they can’t cope…” Such broad statements are what seemingly pit black culture against police authority, a sentiment to Police Chief Daryl Gates (at the time) responded by calling the anti-gang sweeps “a war on ‘the rotten little coward’” (Tranquanda). The LAPD’s direct targeting of N.W.A.’s music, because N.W.A. had been receiving publicity for their breakout hit “F*** tha Police,” led to their album being banned from publicly broadcast radio stations after the FBI wrote in a warning letter to N.W.A. that “Advocating violence and assault is wrong” (King 103). However, N.W.A.’s message spread as far as Illinois to an unlicensed radio station called “Black Liberation Radio,” operated by Mbanna Katako (Rodriguez 194). Now retired Police Sergeant Larry Courts warned N.W.A. against playing the song at a concert in Detroit, and when they started the song, the police “immediately jumped on the stage and started taking out amplifiers” (Counts). Courts said this is “when the problem started,” as 18 people were arrested after the police incidents (Counts). This demonstrates the popularized situation in which N.W.A. believes that the lifestyle they choose to portray is not the locus of the problem, but rather, the problem resides in the public reaction to them from authority figures.

N.W.A.’s aggressive attitude and explicit content may have been what catapulted them to national recognition, but Straight Outta Compton delivers several underlying themes pertaining to life on the streets, the economic conditions of those in Compton, and the misconception of their content being “gang-related.” The 1980s are known as the era of “Reaganomics,” a trickle-down economic program in which “the poor are (getting) poorer and the rich are (getting) richer” (United Press). In contrast to the typical urban town, Compton was, as described my Mike Davis in 1994, a city with a higher homicide rate than Detroit, the highest school dropout rate in California, and was the only city “ever invaded and occupied by the Marines” (Davis 268). N.W.A. makes it a point to illustrate that these conditions were not of fault to the black community, but because their city has a predominance of black people who are unfairly treated, which is boasted by MC Ren’s line “… the n****s on the street is a majority.” Economically,

“…the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan to the White House amid a crippling recession ushered an era of sustained federal budget cuts and a widening rich-poor gap that dealt significant damage to urban areas like South Central Los Angeles.” (McCann 370)

Ice Cube takes that economic perspective and entwines race with the matter, going on to say “A young (brother) got it bad ‘cause I’m brown.” Although some argue that N.W.A. itself was a group that promoted gang violence, they are aligning their musical parody of violence with the reality of violence that N.W.A. believes that they and the black community are subjected to. N.W.A.’s intended purpose can best be summarized by the following selection by Brian McCann:

“…a properly gangsta posture toward our nation’s continuing crisis of incarceration can enrich public discourse by encouraging citizens to take the mark of criminality less seriously and, perhaps, see their criminalized neighbors in a new light” (McCann 381).

The violent themes employed by N.W.A. are merely insights to the reality of the social, political, and economic situation in South Central Los Angeles in the 1980s. N.W.A.’s impact on political rap music stood out at a time when most of America believed police brutality to be a minor issue, which is especially significant considering the album was released before the Rodney King beating on March 3, 1991. N.W.A. received much social disapproval, like in 1989 when Dean Askew, a counselor for the anti-gang group Street Smart, said “their message is destruction” (Briggs). When a critic looks at lyrics like “when I’m called off, I got a sawed-off, squeeze the trigger and bodies are hauled off” from Ice Cube in “Straight Outta Compton,” one would assume Askew’s perspective to be correct. However, N.W.A. vocalizes the lifestyle that they have been born into, not one taken by choice. The ultimate metaphor of the album is that subjugation to unfair treatment, corruption, and police brutality have forced them to threaten people and authority figures with criminal-like behavior in order to have equal treatment. Regardless of the intent of N.W.A., their album Straight Outta Compton is undoubtedly one of the most prominent protest albums pertaining to police brutality, and gangsta rap albums with significant societal impact.

Works Cited

Primary Sources

N.W.A. Straight Outta Compton. Ruthless Records, 9 Aug. 1988. CD.

N.W.A. “F*** tha Police.” Ruthless Records, 9 Aug. 1988. CD.

N.W.A. “Straight Outta Compton.” Ruthless Records, 10 Jul. 1988. CD.

Secondary Sources

Briggs, Bill. “Police prepare to avert rap concert violence.” The Denver Post 29 July 1989: NewsBank – Archives. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

Counts, John. “Retired Detroit sergeant recalls telling N.W.A. they couldn’t play ‘F*** tha Police’ at 1989 concert.” Kalamazoo Gazette: Web Edition Articles (MI) 27 Aug. 2015: NewsBank. Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

Davis, Mike. “The Sky Falls On Compton. (Cover Story).” Nation 259.8 (1994): 268-

271. Academic Search Premier. Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

King, Aliya S., and Miles Marshall Lewis. “The Chronicles of Compton.” Ebony 70.10 (2015):100. MasterFILE Premier. Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

McCann, Bryan J. “Contesting The Mark Of Criminality: Race, Place, And The Prerogative Of Violence In N.W.A.’S Straight Outta Compton.” Critical Studies In Media Communication 5 (2012): 367. Academic OneFile. Web. 27 Oct. 2015.

Roberts, Dorothy E. “Race, Vagueness, And The Social Meaning Of Order-Maintenance Policing.” Journal Of Criminal Law & Criminology 89.(1999): 775. LexisNexis Academic: Law Reviews. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

Rodríguez, Luis J. “Rappin’ In The ‘Hood.” Nation 253.5 (1991): 192-195. Vocational and

Career Collection. Web. 29 Oct. 2015.

Tranquada, Jim. Daily News Staff, Writer. “1,370 Arrested in Anti-Gang Sweep; Crackdown Nets 293 Suspects in Valley; Drugs, Weapons Seized.” Daily News of Los Angeles.

(CA) 13 June 1988: NewsBank – Archives. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

United Press, International. “‘Reagan Record’: Poor Poorer, Rich Richer.” Philadelphia Daily News (PA) 16 Aug. 1984: 62. NewsBank – Archives. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

Austin Goodwin